We make animations, motion graphics and illustrations for your audio-visual communication needs.

Phone: +357 99 658134

Email: info@theoneandahalf.com

One And a Half

28 General Timayia Avenue Kyriakos Building - Block A - Office 301 Larnaca, Larnaca, 6046

Taking the first steps on research communication can be a daunting task. How can we take our results, the fruition of years of hard work, and assure that they are easily understandable to the wide world? The first step is knowing what methods you can turn to. Then, you can start recognising which are best suited to your personal style and your audience’s preferences.

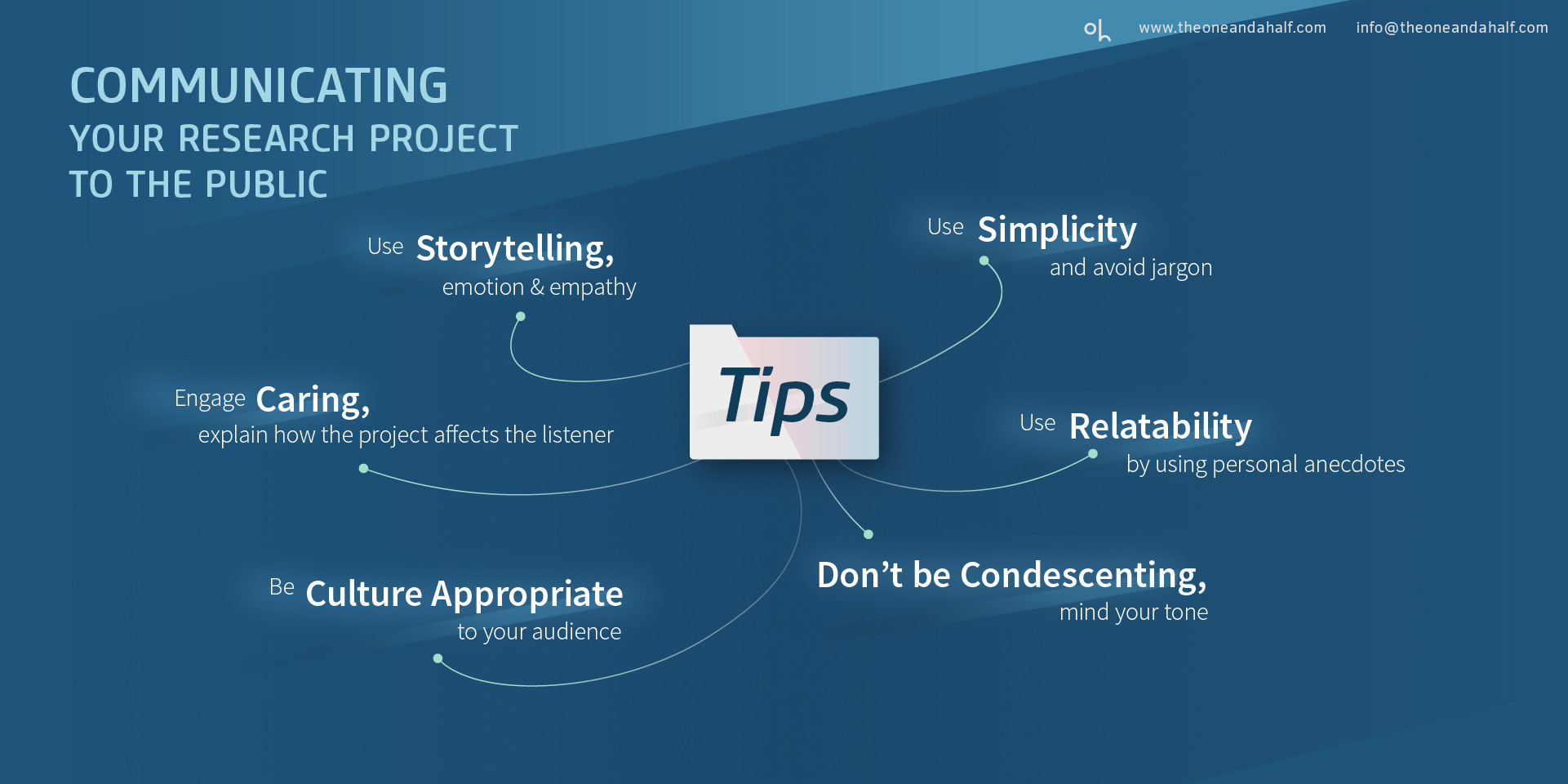

General communication tips to keep in mind:

- Tell a story that people can relate to;

- Don’t overdo it;

- Don’t oversimplify;

- Be as clear as possible;

- Explain why the audience should care.

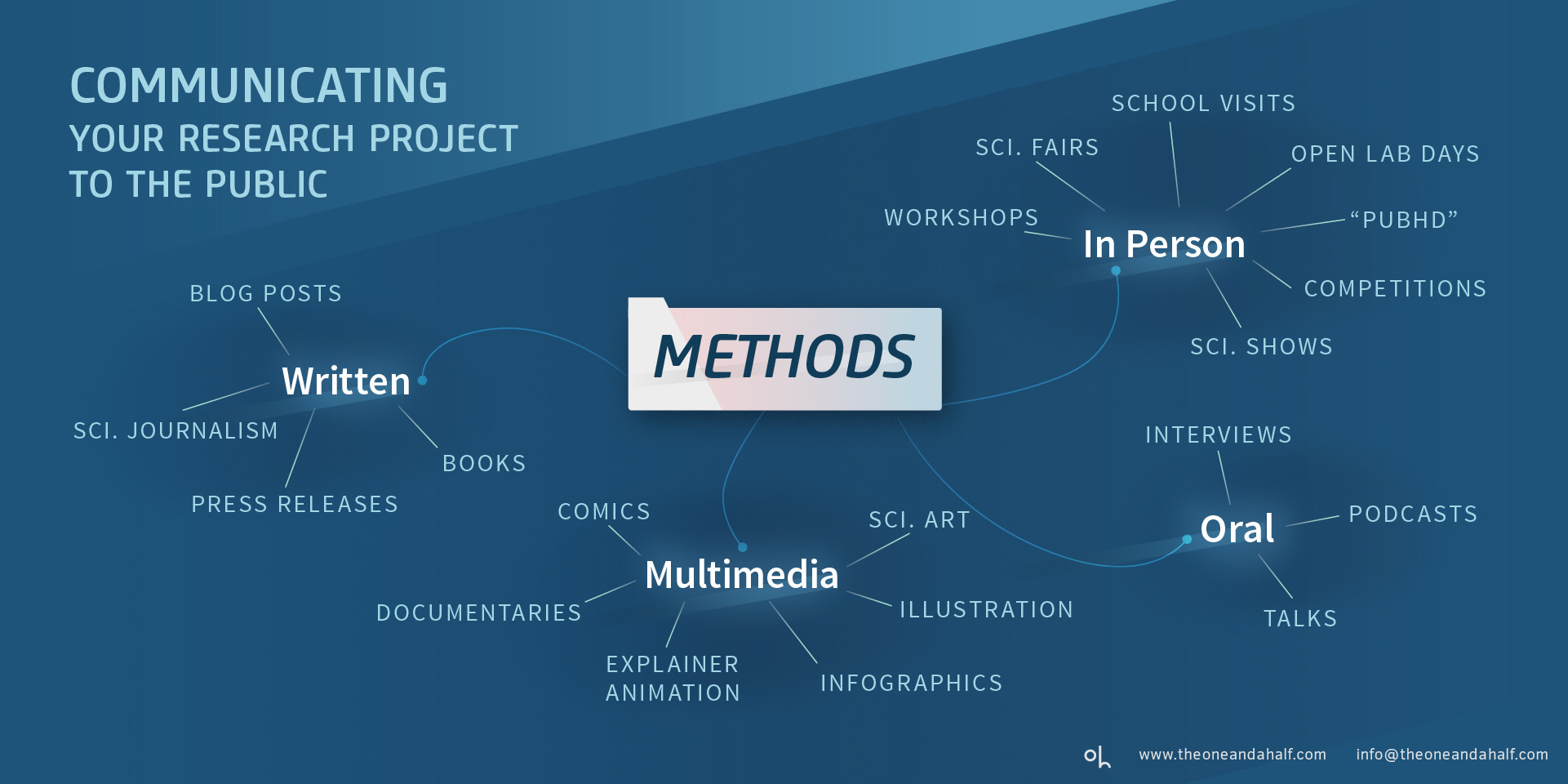

How can we communicate research?

- Written pieces;

- Multimedia formats;

- Oral methods;

- In-Person outreach.

Things to remember when choosing your method:

- How much time and money do you have to invest?

- It is normal to feel overwhelmed.

Outreach activities are of the utmost importance for the development of the scientific field. A solid communication plan can be decisive for a project’s funding approval. It can have direct impact in a community and it may also contribute with ideas to improve the research itself.

Communicating the project and its results should be an essential part of every researcher’s work. But how can we communicate research, exactly? How do we convey something as intricate as our life’s work, in a simple and captivating way? How do we compress months, years of sweat and tears into a small pill of knowledge ready to be swallowed by an audience?

Let's clarify what we are talking about. As explained in “Do you want to write a winning research proposal?”, research outreach can be categorized into:

- Communication - a dialogue with the general public;

- Dissemination - scientist to scientist;

- Exploitation - application of your findings.

In this article, we are focusing on research communication for a wide audience, thus putting dissemination and exploitation on hold.

How this article is structured:

First we will tackle the basics of Science Communication, followed by a list of media we can use,

At the end of the page, you will find more resources to dive deeper into these subjects.

How to be a good communicator

Some good news: in Science Communication, we are not tied by the limits of an academic writing style. As Bora Zivkovic put it in Scientific American, when describing the typical research paper:

"And the personal was so carefully excised for the purpose of seeming unbiased by human beings that it sometimes seems like the laboratory equipment did all the experiments of its own volition”.

Sterile writing will not keep an audience engaged. A riveting account of all the statistical tests you had to run will probably scare your audience away. If you don’t know where to start, look at the tips below on how to present research to a general audience.

They are powerful tools to engage an audience and nurture curiosity. If we were asked how to make an audience trust us, we would say ”with hard facts” or “scientific literature” or “practical evidence”. Curiously, studies show that emotion and empathy, not scientific facts, builds the audience’s trust. We reflect on the importance of emotion and storytelling in one of the following articles in this series, “Animating Science Communication”.

This means avoiding jargon, using shorter sentences and simplifying your message.

Give preference to the active voice. “The scientists studied the cells.”

And use the passive voice sparingly. “The cells were studied by the scientists.”

There are some great ways to make content relatable and interesting. Use personal anecdotes, similes and metaphors. Take advantage of personification to pass a message easy to understand.

One of the biggest difficulties in Science Communication is to simplify your explanation without sounding snobbish. The tone with which you write or speak can go a long way in this aspect. The goal is to be clear without “dumbfying” the subject. Try to vision yourself as part of the audience. If you were hearing about a topic outside of your domain, what would help you to understand it?

Another essential, and often overlooked, detail when communicating research is the effect of culture and context. As Dr. Nat Kendall-Taylor, a psychological anthropologist, puts it in his TED talk, the framing of information matters. Culture - “a shared set of patterns of thinking and assumptions we [...] use when we are presented with information”, influences how we interpret a message. What for us may sound as 2+2=4, in the mind of others may sound as 2+2=6, or 9 or 3000. Remember this when choosing references to illustrate your hypothesis.

A good communicator knows that, when explaining research, it is their job to make the audience care. Do not assume that your public is as interested in mycorrhizae, quantum geometry or the applications of the Markov Model as you are. I must admit I have fallen into this fallacy; going on rants about neuroscience with “non-sciency” friends, while they vacantly stare at me wondering why I find this fascinating. Sometimes, we need to nudge our audience into caring. To do this, always try to answer the questions:

- “Why does this matter?” - how does this impact our society;

- “Why should anyone care about this research?” - does this affect the listener;

- “Why is this relevant today” - tie it in with current issues in society.

There are many ways to deliver knowledge

Pick your tool

It is possible to effectively translate science without diluting the message, and this is why we must know how to adapt our communication strategy. Research Communication comes in all shapes and sizes. Trying to categorize each existing method would be impossible, so we propose the following division.

The most common form of research communication consists in written articles unveiling recent discoveries, explaining phenomena or discussing politics, practices and beliefs.

a. Blog posts - like this one. Hopefully, a stellar example;

b. Science Journalism - Often obtainable through another form of written SciComm: Press Releases. Journalistic pieces are great for exposure, but you have to explain your research simply and straightforwardly. As the journalist is rarely an expert in the researcher’s field, it is easy for information to get lost in translation. Often, only the discoveries deemed “newsworthy” are covered, which can lead to the neglect of basic research;

c. Press Releases - Usually written by the Communications Office at a researcher’s institution, it helps to bring attention from the local media to a new finding or publication;

d. Books - Probably the most time consuming, but where you get to expand on your message the most, while also playing with the writing style.

Visual and audio formats create an intricate piece, which is much more appealing than a long text or lecture. We remember 80% of what we see and do, opposed to 20% of what we read. Visuals embody abstract concepts and complex processes, making them easier to understand and assimilate. Here are some examples:

a. Comics - attractive and entertaining, comics cater to all ages;

b. Documentaries - an in depth dive into a particular topic, with the right script, it can make anything fascinating;

c. Explainer Videos and Animation - Engaging, eye-catching and easily shareable, this form captures more attention than static images;

d. Infographics - As Gareth Cook puts it in his book “Best American Infographics 2013”, there are questions “that demand visual answers”. Infographics allow for the visual representation of numbers and statistics and require a short amount of time to assimilate. Online tools like Canva.com are great ways to get started;

e. Illustrations - these visually appealing images are also highly versatile. They can evoke emotions, accurately represent structures in live sciences or depict anatomy through schemes. They can embody the abstract in economy or the unquantifiable in physics. Illustrations are also great compliments to written pieces.

Albeit great options, these mediums are difficult to master. one and a half specializes in animation, infographics and illustrations, helping to transform your inspiring research into eye catching designs! Great SciComm is a team effort, so reach out if you want help designing your own piece.

Nothing is more accessible than verbal communication. Rich in texture and subjective meanings, it gives ample space for add-ons and personality.

a. Talks - Who hasn’t ever seen a TED Talk? With the help of a great script and on-point visual aids, talks are a powerful way to connect with the public and pass a message.

b. Podcasts - A great way to deliver information for those who only have time while multitasking, Podcasts have exploded in the past years. Yet, they require some investment at the beginning.

c. Interviews - Another option to show your human side while advocating for your focus topic. Look for blogs or journalists that usually report on your topics of interest.

The most dynamic way to interact with your audience. It requires high commitment and planning, but it can be the most rewarding. You can see the impact of your efforts almost immediately. A necessary Pandemic disclaimer: these are adaptable to digital formats!

a. Workshops;

b. Science Fairs and Festivals;

c. School visits;

d. Open lab days - showing exactly what you did to get to a conclusion can be the best way to install confidence in the audience;

e. PubhD, pint of science - these communication activities bring scientists and audience to the intimate setting of Pubs and cafes, where the expert explains their research while the audience enjoys a nice beer (or any other drink of their choosing);

f. Communication competitions - we keep inventing new ways to challenge ourselves. Fame Lab may be the most famous, yet it will be hard conveying your research in this format. It focuses on basic science concepts. Three minute thesis competition gives three minutes for researchers to explain their research project, so is less attainable for a lay audience;

g. Science shows - Who hasn’t heard of Bill Nye, the Science Guy? Shows have big production value, so if you are looking to cause an impact, you have your option right here.

Consider your needs before choosing a method

Before choosing the communication format you want to use, ask yourself what your goals are.

- Why are you communicating your research?

- Who do you want to reach?

- What do you expect to happen after you do your initiative?

Based on the answer to these questions, you can start to match your needs to what each format can deliver.

If you want a bigger reach, guest post on a big blog or reach out to local newspapers and television for an interview. Organise a workshop or join a science fair to inspire a younger generation. If you want to raise awareness for the disease you are studying, maybe an infographic or explainer video will do the trick.

Choosing the right method also depends on how much time and money you are looking to invest. Science shows are fun and raise plenty of attention, but you will have to spend a lot on materials. You will also have to create the content and find the time and place to perform. Writing a long piece may be cost effective, but getting the words in your head to flow in the page (or screen) can be time consuming.

Rome was not built in a day

Remember that it is normal to feel out of your depth. Technical skills, such as animation or videography, take years to learn. Giving public talks is an art of its own. Thinking translationaly doesn’t apply only between Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics disciplines.

Asking for help when you are outside of your comfort zone is logical and can even drive you to learn new skills. Professional science communicators and skilled artists all around the globe. These professionals are ready to lend you a hand and help you make the best of your work.

When you know how to make the best out of your knowledge, you can start putting pen to paper, voice to microphone, stylus to drawing pad or fingers to keyboard. You can put your findings to use and make your research reach far and wide. Read our article about adapting SciComm to an audience, and you will be ready to try your hand at Science Communication!

Further resources:

- Greg Foot youtube channel - free introductory course on SciComm: https://www.ascb.org/science-policy-public-outreach/science-outreach/communication-toolkits/best-practices-in-effective-science-communication/

- How to make writing concise, yet interesting: https://medium.com/@scottydocs/what-is-the-perfect-sentence-length-4690ce8d5048

- More tips to communicate science to a non-expert audience: https://www.scientifica.uk.com/neurowire/tips-for-communicating-your-scientific-research-to-non-experts

- How to give a successful talk: https://greenfinstudio.com/2019/04/04/science-communication-ted-talks/

- Some Podcast inspiration: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02096-4

- SciArt examples

- Sound: http://www.stemartslab.com/sci-art-installations/

- Interactive art: http://www.sciartinitiative.org/group-2-stefanos--diaa

- Examples from the past decade: https://blog.scienceborealis.ca/sciart-favourites-from-the-past-decade/

- Poetry: http://www.sciartinitiative.org/group-3-geetha--ben/week-15-geetha-ben

- SciComm initiatives:

-

- Chat with students about science: https://imascientist.org.uk

- Art dives into SciComm: https://www.sciartmagazine.com/collaboration-art-and-science-methods.html

- Creative methods for research communication: https://www.researchretold.com/creative-met

At one and a half, we are passionate about research communications and getting your findings seen.

If you are curious about how your research project can benefit from animation, contact us today for a free consultation at info@theoneandahalf.com OR here.

We thank these lovely ladies for their collaboration

Illustrations and infographics by Christina Kalli.

Written by Antónia Ribeiro

Antónia Ribeiro Bio

Antónia was a Biologist, once upon a time. She transitioned from the glamorous world of lab benches and international conferences to her one true love - Science Communication.

Portuguese by birth, Antónia is based in Malta. Besides being a freelance science writer, she works as a Social Media Manager for a research magazine and manages an Erasmus+ project for strategic partnerships.

Antónia has a Bachelor in Biology and a Master’s in Biomedical Research from the University of Coimbra, in Portugal. In her free time, she pets street cats and educates people on Portuguese gastronomy - often against their will.

You can find her on Linkedin.

02 December 2021 by theone, in Article-Rescomm

02 December 2021 by theone, in Article-RescommWhat is Horizon Europe

Horizon 2020 is being continued and improved through Horizon Europe, up until 20...READ MORE + 22 September 2021 by theone, in Article-Rescomm

22 September 2021 by theone, in Article-RescommAnimating Science Communication

Once you finish reading this page, around 300 hours of videos have been uploaded...READ MORE + 16 May 2021 by theone, in Article-Rescomm

16 May 2021 by theone, in Article-RescommHow to evaluate your SciComm Project

Scicomm evaluation ➡ 1.Decide your goal | 2. Set your objectives | 3. Consider y...READ MORE +